Robert Magyar, Managing Director, Sandpiper Health Talks to Telum

Rob van Alphen Joins Sandpiper to Lead Customer Journey Offering

Winning PR Strategies in China for Financial Firms

September 2022

by Tian Zhang, Account Manager, Beijing. Tian specialises in PR for financial services and investor relations. He has broad experience in capital market analysis, corporate communications, reputation management and crisis and issues communications.

It’s where a third of the world’s population lives, is three times the geographic size of India, and not only are its cities and regions vastly different – they are very specific in how they operate.

Understanding China’s uniqueness and its vast internal differences can help unlock a wealth of opportunities for multinational financial institutions wanting to enter and succeed in this market.

Given its size, economic growth and influence in the region, when it comes to building brand and reputation, it’s imperative for financial institutions to have a dedicated, standalone strategy for the Chinese market to be successful.

The Case for an Asia ex-China Approach

In the past decade, many financial institutions have implemented a Greater China or China standalone strategy for their investment mandates, but communications strategies have lagged behind, with many still applying an Asia Pacific (APAC) or Asia overall approach.

The concept of Asia ex-China is akin to the ‘Asia ex-Japan’ approach used by many investment banks and research houses in finance, which traces its roots back to the 80s and 90s when Japan was the most dominant player in Asia. However, since China surpassed the GDP of Japan in 2010, it would seem an Asia ex-China approach should be the new norm.

Addressing Compliance Hurdles in China

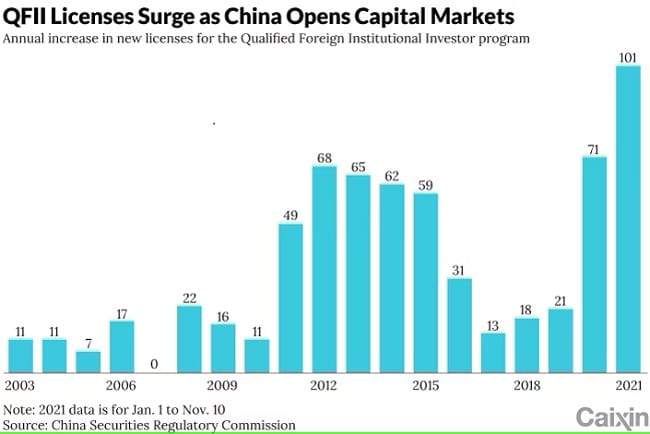

The Asia ex-China approach is also evident in financial institutions’ compliance teams, most having in-house counsel which is country-specific instead of region-specific. Despite China’s continued financial opening-up which has seen foreign ownership ceilings raised, approvals for foreign institution licenses increased and the development of numerous cross-border stock and bond connect schemes, many foreign financial institutions are still in the process of obtaining their license to operate and sell financial products/services in China, which raises concerns for compliance teams in China.

As such, the lack of a China license often leads foreign financial institutions to wonder about their China communications approach. Crafting messaging that builds brand reputation, highlights global expertise, and promotes thought leadership, while allaying compliance concerns can be done; but it requires extensive know-how and a thorough understanding of China’s media landscape and the regulatory framework of China.

This is where a standalone China communications strategy in tandem with a team that understands the internal stakeholder structure of financial institutions can be a great advantage.

Understanding the Chinese Culture

In addition to compliance considerations, cultural considerations are also a make-or-break issue. The iconic example of McDonald’s vs Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) in China is well known, where China is the only market in the world KFC outperforms Mcdonald’s.

Simply put, KFC’s success in China comes from its idea of family feasts and shared buckets that resonated well with Chinese consumers and reflected Chinese culture. McDonald’s on the other hand entered the market mainly promoting Western ideals around food service and dining rituals and is now playing catch-up with its own family-orientated offerings.

While consumer brands are worlds apart from financial institutions, the above phenomena highlight the need for any foreign player, including financial institutions, to be armed with the right market insights before undertaking any activities, and to have the right messaging and products localised to China. Being a big name domestically and in other markets isn’t enough.

Understanding China’s inherent culture and how it influences investment goals and risk profiles is critical for implementing a successful communications strategy. The same investment ideals and wealth management approach that other Asian countries ascribe to may not resonate with Chinese investors. As such the messaging surrounding these also needs to be tailored to the Chinese investment community.

Understanding China’s inherent culture and how it influences investment goals and risk profiles is critical for implementing a successful communications strategy.

Earning Media Coverage in China

Chinese journalists, like journalists elsewhere, are always looking for locally relevant, timely, and objective stories that are based on fact and not self-serving. With an interesting angle or content that aligns with the national narrative or even a more micro-regional story, some journalists will be eager to cover the story.

But one significant difference between Chinese journalists and their foreign counterparts is the morning editorial meetings. All media outlets in China receive a daily decree from the Government, advising what will be reported on and published that day. Having attended many of those meetings during my time at China Daily, it is clear that to get a breakthrough, it is about understanding what journalists need and how news editors will think about the news piece being pitched.

The way Chinese news editors will consider a story involves the following core aspects:

- Pro-China

While the sentiment of a particular news story should inherently subscribe to this value, it does not have to be all pro. To give an example if GDP growth is slow, the article could go ahead if the focus is more on the future implementation of policies that will help boost GDP. It is very rare that an entire topic will be vetoed therefore it is about looking at a potential story differently from a western angle.

- Focus on the long term

The future is very important to China and short-term stories aren’t always on the cards. The way the entire system is structured is on continuity and Chinese media are more likely to report on implications 5-10 years in the future. For example, a financial institution may look at commenting on rate cuts affecting the next two months, while important, without the long-term view, journalists and their editors will likely disregard the comment.

- Stay relevant to and connected with the local media landscape

Another key consideration that financial institutions must take is from the media engagement strategy perspective. It’s imperative to understand the hot spots for any story that is planned to be shared. Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen stand out as top-tier cities yet they are all distinct in their functions. Beijing is the Government policy hub, Shanghai is the financial hub, and central China is more industry-focused.

For example, a financial institution targeting the Greater Bay Area (GBA), should consider reporters based in Shenzhen and Guangzhou more than Beijing or Shanghai for optimal results. This requires any communications team to have a comprehensive media network that spans China’s large geography. Maintaining this media network requires significant resources and investment, which is in contrast to a country like South Korea, where 90% of its GDP is generated out of Seoul, with the rest of the country essentially for living.

Newsjacking on China’s regional-specific news and elevating the message to a broader Chinese context works well in achieving most companies’ objectives and is the common writing style of Chinese journalists. Other content that resonates well with journalists are industry research reports, data-driven insights, and forward-thinking commentary -with a clear China-specific angle.

Additionally, providing reporters with a transcript also goes a long way in earning media coverage, and the benefits are two-fold. An approved transcript will boost the ability to generate coverage from any media engagement and also allows companies to fine-tune their messaging before sharing with the press.

Transcription and translation services also need to be budgeted for in China – while English is a mandatory second language in China, proficiency still lags in the likes of Singapore. As such, when planning the PR strategy for China it is important to also factor in costs such as translation of collaterals, simultaneous interpretation as well as stenography.

Mistakes of the Past and a Glance to the Future

Many companies have missed the mark when engaging the China market over the years in terms of their communications strategies. HSBC’s 2009 costly ‘Assume Nothing’ campaign which entered the Chinese market as ‘Do Nothing’ is an iconic example. Likewise in the 90s, Australian brewing company Fosters fell flat on its China market entry, adopting a phonetic translation of its name, which ended up meaning ‘Fuji Mountain Beer’.

Foreign financial institutions entering China have learned some things from their predecessors, but the strategy is vital to move with the times. And China is moving so quickly. The digital world is changing dramatically and policy monitoring should take place daily so messages can be structured correctly. Because policy dictates what media can write about, financial institutions need to be in the know and armed with relevant market insights

But while there is constant change and transformation taking place in China at speed, the foundations around what Chinese people want and do are centuries old. For financial institutions looking to build a brand and reputation in China – it’s the play on top of the foundations where the real opportunities lie.

Sandpiper’s regional financial services team has experienced financial communications practitioners located in six commercial hubs in the Asia Pacific region. We use our specialist knowledge to navigate the financial landscape and deliver strategic communications programmes for our clients to drive growth. Get in touch