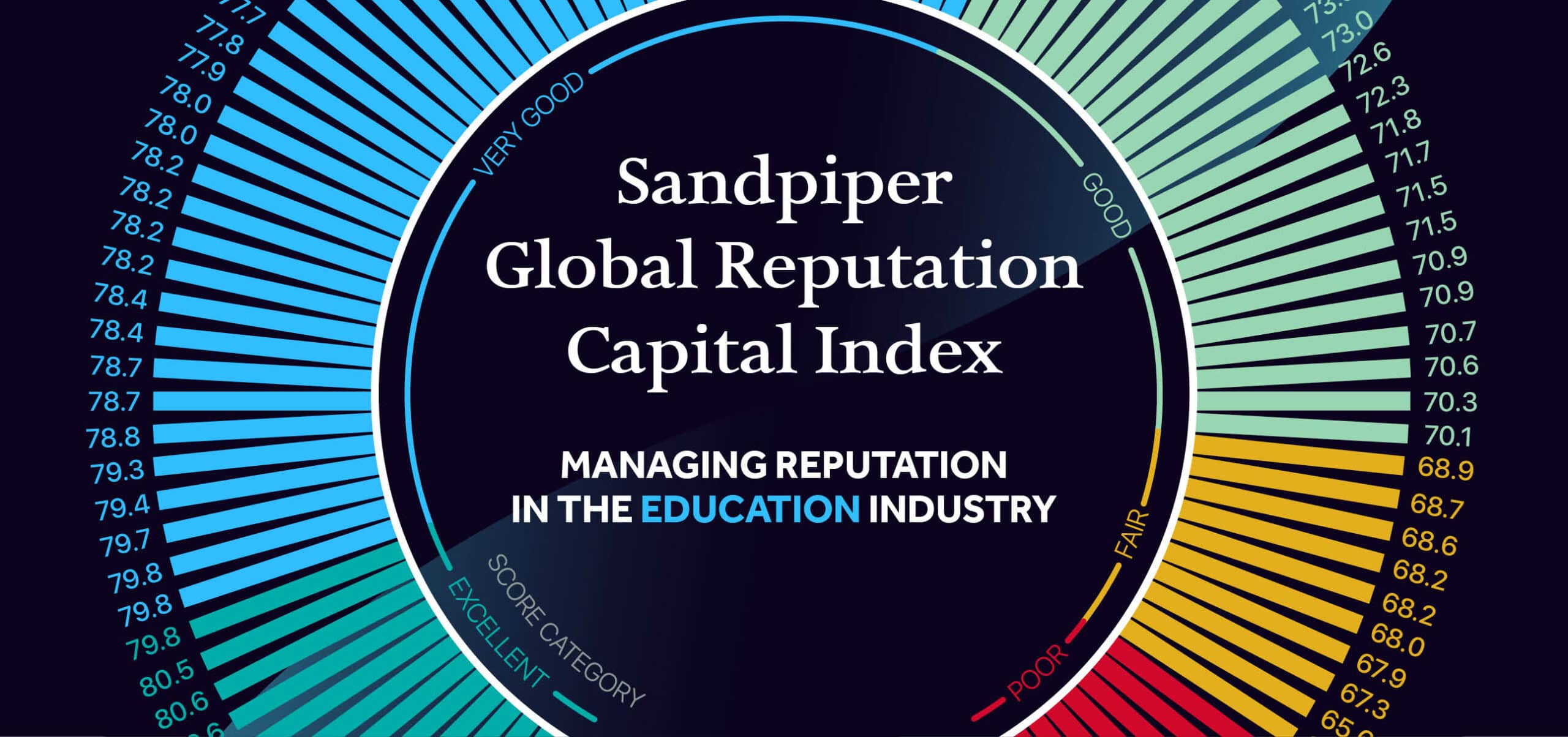

Launching the Sandpiper Global Reputation Capital Index: Managing Reputation in the Education Sector Report

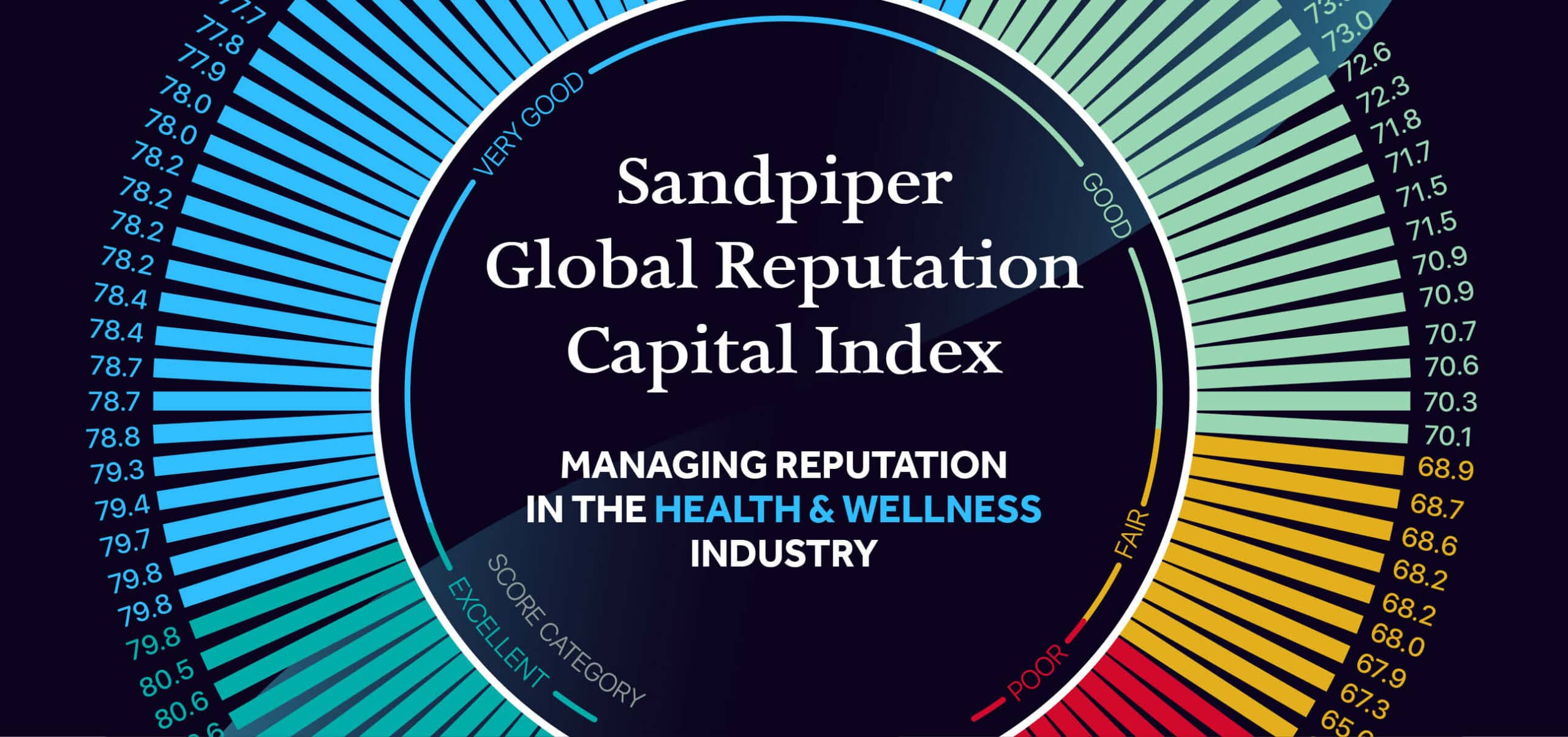

Launching Sandpiper Global Reputation Capital Index: Managing Reputation in the Health & Welness Sector Report

Using Psychology to Communicate Preventive Health Strategies

February 2025

This article was contributed by the Sandpiper Health editorial team. Sandpiper Health is a specialist consultancy under Sandpiper Group, providing in-depth monitoring and analysis of the healthcare and life science sector, and helping pharmaceutical and medical technology companies, healthcare providers, patient and caregiver groups, as well as investors and professional organisations formulate effective stakeholder engagement strategies to achieve their business and communications objectives. To receive regular insights from Sandpiper Health on healthcare trends and policy updates in Asia Pacific, sign up to Asia Pacific Healthcare Outlook Monthly Newsletter.

- Health outcomes and behaviours are strongly intertwined, alongside other factors such as genetics, socioeconomic factors, and access to care

- Using behavioural economic principles, a subset of behavioural science, can help communicate effectively to target audiences and shape their health behaviours

As global populations grow older, governments are increasingly focussing on preventive health, encouraging citizens to take charge of their health before the onset of disease. From screenings to information sharing and counselling, the goal is to identify health issues before they develop. Preventive health measures can also ensure timely intervention before diseases progress, reducing the burden on both individuals and health systems.

The success and efficacy of preventive health measures is highly contingent on people’s behaviours, which can be complex. How people behave in relation to their health is influenced by many factors, such as their beliefs, values, perceptions, personality, behaviour patterns, actions, and habits. These are essentially the areas explored in behavioural economics – the psychological study of people’s motivations for making decisions and how these can diverge from rational behaviour.

Communicating preventive health practices effectively involves thoughtful, tailored, and culturally appropriate messages, but behavioural economics offers the potential to go further. Cleaving to relevant behavioural economic principles can ensure that messages get through and support the health outcomes we hope to achieve. Here we explore a few of the most relevant behavioural economic principles for preventive health communications strategies today.

Optimism bias

Most of us tend to overestimate our likelihood of experiencing positive events and underestimate our likelihood of experiencing negative ones – this is called optimism bias. Our perception of risk is a key element in preventive health behaviours, and studies have shown that in many situations our view is distorted. During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers found that people who perceived their risks as lower for catching COVID were less likely to feel fear and anxiety about the disease. To reduce optimism bias, campaign messaging should always strive to reinforce current risks.

Availability bias

People frequently use this mental shortcut to form impressions or make decisions, prioritising information that comes to mind quickly rather than basing decisions on evidence. To combat this very human tendency, communications through each channel need to be consistent and engaging, giving people accurate material over a sustained period to ensure quick recall of a relevant topic or issue. For instance, when promoting screening campaigns, communications should be consistent across channels – making it more likely target audiences will know the information and remember it in crucial situations, e.g. before a doctor’s appointment or when it is time for a health check-up.

Prospect theory / loss aversion

According to prospect theory, people make decisions that involve risk and uncertainty based on “loss aversion”. Their decisions are motivated more by the fear of potential loss than the prospect of equivalent gains. Thus, showing people what they risk losing through harmful behaviours or inaction can often be more motivating than, for example, extolling the benefits of a healthier lifestyle.

Another way to think about this phenomenon is simply that many people do not have high health “aspirations”. For this reason, health campaigners are increasingly drawing away from using professional athletes as figureheads for health campaigns, recognising that people need to connect with risks and rewards that are relevant to their lives.

Harnessing the messenger effect

The perceived credibility, expertise, or likeability of a messenger can influence how information is received, interpreted, and acted upon. This should deeply influence the choice of who communicates a message. For example, a recent study tested the effectiveness of government messengers to encourage preventive health actions during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. It found the impact was limited, but public health organizations are universally perceived as more trustworthy, relevant, and competent than anonymous messengers.

Health behaviours are complex and multi-faceted. There is no one-sized-fits-all approach when it comes to communicating preventive health strategies – but incorporating key behavioural economic principles into communication strategies can drive more effective engagement. Factoring in psychology and deploying strategies from behavioural economics can help encourage more people to adopt preventive health approaches and practices, leading to healthier populations everywhere.