Ignore the Moral Panic and Embrace Fact-based AI Governance

How Can Businesses Be Involved in Policymaking That May Impact Their Business

Elderly Care Across Asia Pacific

July 2023

With overall social development advancing, the number of elderly people in the Asia Pacific region is rising at an unprecedented rate. While increasing longevity is a positive outcome of social, economic, and technological development, a rapidly aging population can be a challenge, not only to pension systems but also to sectors including health, finance, long-term care, social protection, education, labour, housing, transport, information, and communication.

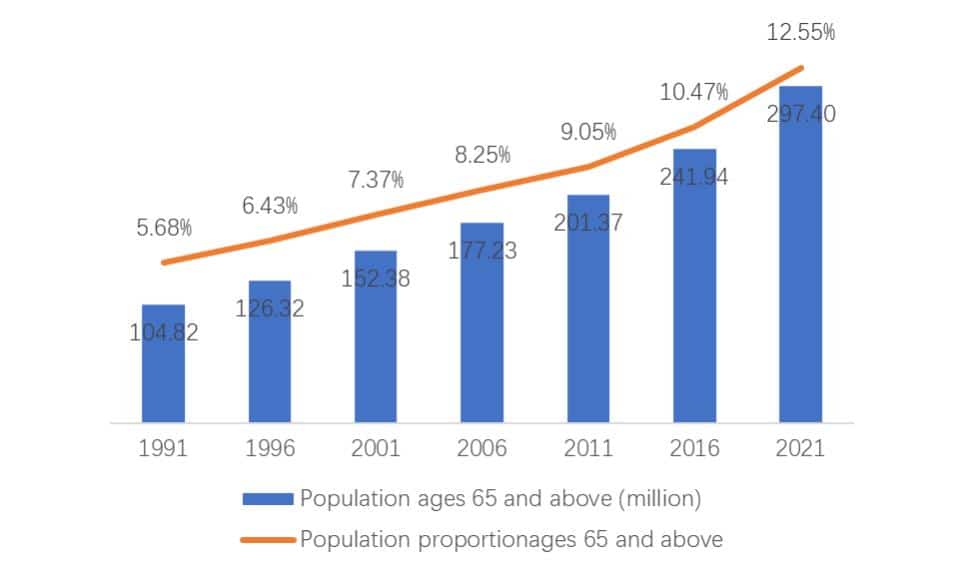

The World Bank’s statistics below show that the population aged 65 and above had nearly tripled in the past 20 years, reaching 297,402,740 in 2021. This trend will continue throughout the first half of the 21st century. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), by 2050, one in four people in the Asia Pacific region will be over 60 years old. The population of older persons (aged over 60) in the region will triple between 2010 and 2050, reaching close to 1.3 billion.

Figure 1: The growth trend of the elderly population in the Asia-Pacific region over the past 30 years

Regional policy overview

As the world’s most populous region with a rapidly ageing population, elderly care is a growing concern for policymakers in the Asia Pacific region. Different territories are taking different approaches, but many have recognised the importance of creating new biopharmaceutical and technical healthcare solutions, as well as innovation in the administration and management of elderly care systems. Noteworthy highlights include:

- China: China faces increasing concerns regarding population ageing and healthcare. Its one-child policy (1980-2015) resulted in smaller families being increasingly relied upon to support many elderly people, while a growing number of elderly individuals are now living alone. China’s National Health Commission has projected that the number of individuals aged 60 and above will surge from its current number of 280 million to 400 million by 2035. Consequently, the demand for beds in community facilities and nursing homes is expected to rise from the current eight million to approximately 40 million. To foster the well-being of its senior citizens, China has implemented several policies and initiatives designed to improve healthcare accessibility, including expanding healthcare coverage, investing in infrastructure and technology, and promoting innovation. In May 2023, the Chinese government issued guidelines mandating all provinces to provide essential elderly care services, including material assistance, nursing care, and caregiving services by 2025.

- Singapore: Singapore is rapidly transforming into an ageing society, with a Singapore Institute of Management projection indicating that one out of every four inhabitants will be aged 65 or older by 2030. To cater to an ageing population, Singapore has introduced its latest healthcare initiative, Healthier SG, which aims to offer preventive care for chronic ailments such as hypertension and obesity. Through the provision of a family physician and a health plan for every individual, Healthier SG advocates for fostering robust bonds between family doctors and patients and offers customised healthcare plans that are tailored to individuals’ specific health needs. In conjunction with Healthier SG, Singapore’s Ministry of Health has launched the LumiHealth mobile app, which employs AI technology to provide health and wellness assistance to the elderly population by encouraging a healthier lifestyle.

- Taiwan: The ageing population is a critical social concern in Taiwan. The National Development Council projects that the island will attain “super-aged” status by 2026, with seniors comprising 25 percent of the population. Taiwan’s demographic shift is notably fast, affording policymakers little time to adjust. Data reveals that it took Taiwan just 25 years to transition from being an “ageing society” in 1993, with only 7 percent of the population aged 65 or more, to an “aged society” in 2018, with over 14 percent aged 65 or above. To tackle this accelerating demographic shift, National Cheng Kung University is constructing a geriatric hospital that will be equipped with AI, robotics, and wearable devices to interact with remote elderly patients. These technologies will be utilised to cater to the specific needs of elderly patients and overcome challenges associated with diagnosis, communication, and location.

- New Zealand: New Zealand’s policymakers are faced with the challenge of an ageing population and a decline in elderly care facilities. While the number of individuals aged over 65 is predicted to double by the 2050s to approximately 1.4 million, the number of aged care facilities and beds has recently reduced owing to insufficient staff and funding. To address these concerns, New Zealand’s public health agency, Te Whatu Ora, aims to increase its spending on elderly care by providing support to elderly individuals with dementia and raising salaries for staff in relevant sectors. They anticipate increasing their spending on elderly care from 46 percent of their health budget to 54 percent by 2032/33.

Improving elderly care regulations

Elderly care regulations play a crucial role in providing high-quality care services for older people. These regulations, established by government bodies, aim to protect the rights, well-being, and dignity of older individuals while maintaining a high standard of care within the industry. However, in the Asia Pacific region, there is a disparity in the development of elderly care systems, with low-to-middle-income countries relying heavily on informal care, while high-income countries boast better access to services and higher levels of regulation.

To ensure older people’s quality of life, it is essential to find more comprehensive approaches to regulating aged care services. A robust regulatory framework, including inspections for compliance, and the establishment or strengthening of quality standards, indicators, and staff ratios, is necessary to deliver safe and high-quality care to older individuals. Two key areas where elderly care can be improved are:

- Building multiple levels of responsibility: A multi-level approach to regulating and monitoring aged care services ensures accountability at various levels, from individual facilities to government bodies. This process helps to prevent gaps in oversight and ensures that standards are met consistently.

- Mandatory reporting: Data measurement and public reporting are increasingly being used as tools to monitor compliance. Requiring regulatory inspections, quality care indicators, and outcome data to be reported can drive improvements in the quality of care and overall quality of life for older people. Many countries, such as Australia, are now implementing mandatory reporting and making data collection publicly available to drive improvements in quality.

These approaches and others will continue to strengthen the elder care system in the coming years, bolstering efforts to improve the sector qualitatively.

“Healthy ageing” and the “silver dividend”

“Healthy ageing” has been defined as “the optimisation of functional capacity within the constraints of normal age-related physiological, psychological, and sociological changes.” However, while people are living longer today, they are not necessarily living better.

In the face of a rapidly ageing population, governments and businesses worldwide are investigating and investing in strategies and initiatives that support healthy ageing to ensure that they have a sufficient and productive workforce that can sustain their respective economies.

Furthermore, the United Nations has also marked the 2020s as the “Decade of Healthy Ageing”. The United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing is a global collaboration that was established to allow everyone to add life to years, ensuring that they enjoy good health and well-being. A four-pronged approach has been identified and consists of: 1) changing how we think, feel, and act towards ageing; 2) cultivating age-friendly environments; 3) creating integrated and responsive healthcare systems and services; and 4) and ensuring access to long-term care for older people who need it. In the Asia-Pacific region, governments are establishing policies and investments that align with these strategic priorities.

By prioritising healthy ageing, governments can turn the challenge of ageing populations into a “silver dividend”, an area of unexpected value, by introducing policies for technologies that improve elderly people’s health, extend skills and working lives, and facilitate employment. Improved health and longevity encourage a segment of older workers (aged 55-64) to stay in or reenter the labour force while falling birth rates are forcing countries including China, Japan, and South Korea to delay retirement to maintain working population sizes.

As medical technologies and care options continue to advance, an ageing workforce may no longer be seen as an impediment to an economy’s innovative capacity or economic growth. Five types of technologies can take action to support economic growth by positively affecting the use of enhanced human capital, including:

| Substituting labour and skills | Complementing labour and skill | Aiding education skills development and lifelong learning | Batter matching workers with jobs and tasks | Extending healthy lives and overall life expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – Automation – Industrial and service robots – Robotic process automation | – Physical augmentation – Virtual office and remote work – Collaboration tools | – Online learning courses – Education management systems – Lifelong learning platforms | – Job portals – Social networking job or career sites – Cloud platform for specific tasks – Career guidance | – Digital therapeutics – Remote patient monitoring – Bioinformatics |

To best make use of these technologies, the most suitable policy agenda for a given market depends based on its economic development, level of education, and projected distribution of economically active individuals as of 2050. In Asia Pacific, four distinct profiles can be created based on their speed of ageing and median education levels:

Fast-Ageing, Above Median Education:

These territories are experiencing a radical shift from young low-educated workers to older and more educated workers, such as Japan and South Korea.

Fast-Ageing, Below Median Education:

These territories historically had low levels of education, especially among the younger economically active population, such as Bangladesh and Maldives

Slow-Ageing, Above Median Education:

These territories have a younger population that will complete tertiary education, such as Mongolia and the Philippines.

Slow-Ageing, Below Median Education:

These territories have a slower pace of societal aging and progression of education attainment, such as Cambodia and Nepal.

These group-specific patterns help identify appropriate solutions for each country type. Countries that are fast ageing and have above-median education levels would benefit from adopting automation and labour-augmenting technologies to supplement their low supply of labour for routine work. In contrast, fast-ageing and below-median-education countries need to prioritise policies that build a high-educated workforce and reskill older primary-educated workers. Technologies that aim to boost health and longevity are beneficial to both types.

Looking ahead

As Asia Pacific continues to age rapidly, elderly care will continue to grow in importance as a key aspect of healthcare systems across the region. MNCs are well advised to consider synergies in their product portfolios that match this trend while staying abreast of the latest regulations and national policies affecting this domain. This sector is a critical area to watch in the Asia Pacific region in the coming years.