Navigating Reputation Minefields in 2025: Professional Services Sector

Launching the Sandpiper Global Reputation Capital Index: Managing Reputation in the Education Sector Report

Beyond Labels – Fund Managers Must Think Long Term as ESG Investment Appetite Matures

February 2025

By Joan Ng, Associate Director. Joan works in Sandpiper’s Singapore office and has extensive experience in finance, media, and sustainability.

Money flows suggest the global investment audience is now past peak ESG. This waning enthusiasm for environmental, social, and corporate governance principles comes even in the teeth of stricter standards for ESG labels – raising the question of whether such labels are worth the trouble.

Yet it would be a mistake for fund managers to abandon established ESG investment frameworks. While the rewards of embracing ESG may be debatable, the reputational risks of abandoning it are too significant to ignore.

Furthermore, continued improvement in ESG fund labelling requirements reduces the risk of asset managers being caught in a net of greenwashing accusations and provides greater structure to build reputational capital.

Stricter standards

The term ESG is used to represent a loose set of investment principles, and its application in the asset management industry varies from one jurisdiction to another.

Singapore, for instance, has disclosure and reporting guidelines for ESG funds, but no formal labelling criteria. The fund manager is responsible for assessing whether a fund is an ESG fund.

ESG funds marketed as such in Hong Kong must meet some requirements, but the classification approach is disclosure-based.

The European regime is far more prescriptive. Several countries promote their own labels, which require funds to go through a certification process. Examples of such labels include Luxembourg’s LuxFLAG and France’s SRI Label.

Since November last year, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has also adopted a more stringent set of requirements for ESG funds. The new guidelines require ESG funds to invest a minimum proportion of assets in ESG-related instruments and adhere to some minimum standards.

The ESMA move is a response to concerns over greenwashing and misleading marketing, and reflects a significant step forward for ESG-minded investors. Other jurisdictions could see this as a reason to advance their regulatory regimes too, as investor expectations rise.

Falling from favour

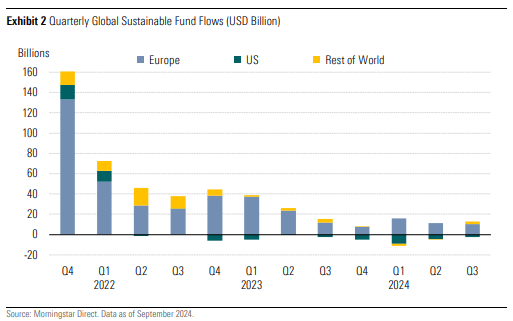

At the same time, investor demand for ESG funds is falling. Morningstar data shows that in the third quarter of last year the global sustainable fund universe – comprising both opened-end funds and exchange-traded funds – recorded net inflows of US$10.4 billion. This figure represents a slight improvement from the Q2 inflow of US$6.3 billion, but still puts inflows on track for a third consecutive down year.

Europe, the world’s largest market for sustainable funds, attracted net inflows of US$10.3 billion. This was less than the US$11.1 billion recorded in Q2. Asia ex-Japan recorded net inflows of US$2.5 billion, down from US$3.1 billion in Q2. The largest net ouflows were seen in the US, to the tune of US$2.3 billion. This was nevertheless a slight improvement from outflows of US$4.7 billion in Q2.

Product development, meanwhile, hit a new low: only 57 new sustainable funds were introduced worldwide in Q3, putting the total for the first nine months of 2024 at 246 funds. In the first nine months of 2023, 444 new sustainable funds had been launched.

Morningstar’s analysts believe the slowdown reflects a “normalisation” after three years of high growth, while also noting that asset managers would have been waiting for the finalisation and implementation of new European regulations. They expect to see a rebound in product development activity for Q4.

ESG is good business sense

Moderating investor demand and product development may be indications of weakening positive sentiment surrounding ESG, but they are more likely to be indications of a maturing market for such investments.

Unlike its predecessor – corporate social responsibility – ESG is not about using investor dollars for charitable purposes or trading profit for philanthropy. ESG investment principles emphasise the risks companies face when disregarding potential negative impacts from factors such as climate change or the exploitation of employees.

In several markets, such as the US, there is a growing backlash against ESG principles. This backlash is sentiment-driven, however, and stems partly from a misunderstanding of what ESG means. Studies show that when properly applied, with an emphasis on financial materiality, ESG principles produce better performance, especially over the long term.

One of the risks built into ESG frameworks is reputational risk. Research shows that news events related to corporate greed, environmental catastrophe, and social injustice tend to have demonstrable financial costs related to negative exposure on social media platforms. These costs, researchers say, are in addition to the physical costs associated with such events.

In the past, sharing ESG credentials brought a substantial risk of greenwashing accusations. But as standards improve, these risks are receding, and the costs of non-compliance could well rise. Looking beyond the labels, the asset management industry would do well to embrace ESG in both agenda-setting and decision-making.